The bar for patenting software is generally higher than for traditional technology. This is mainly due to the fact that “programs for computers” and “mathematical methods” are not considered to be inventions under a legal provision in the European Patent Convention (EPC). This is the intention of the legislator and a political decision. Nevertheless, it is possible to patent software. This whitepaper provides an insight into how software respectively computer-implemented inventions (CII) are dealt with at the European Patent Office (EPO). The information is mainly based on the decision G1/19 of the EPO’s Enlarged Board of Appeal issued 2021. This decision is an all-out attack on CII and provides a good basis for an inside view into the software patenting at the EPO.

Table of Contents

ToggleI. Provisions of the European Patent Office

The basic provisions for computer implemented inventions and all other inventions are set out in Articles 52 and 56 EPC (EPC = European Patent Convention). An issue for computer implemented inventions is that according to Articles 52(2) and Art. 52(3) EPC “programs for computers” as such are not regarded as inventions. In the following chapter, these Articles are examined in more detail, with the information is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 24 to 27.

The first basic article of the EPC re patentability

Article 52(1) EPC:

European patents shall be granted for any inventions, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application.

“All fields of technology” and “Invention” of Art. 52(1) EPC

- The reference to “all fields of technology” was introduced in the course of the EPC’s revision (EPC 2000) to bring Article 52 EPC into line with Article 27 of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). The amendment makes clear that patent protection is reserved for creations in the technical field (see OJ EPO Special edition 4/2007, 48).

- The claimed subject-matter must have a “technical character”, or, more precisely, involve a “technical teaching”, i.e. an instruction addressed to a skilled person as to how to solve a particular technical problem using particular technical means (Please see ANNEX I: Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC, document MR/2/00, page 43, no. 4). It is on this understanding of the term “invention” that the patent granting practice of the EPO and the jurisprudence of the Boards of Appeal are based. In other words, the “technical character” is an implicit requisite of an “invention” within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC.

- The term “all fields of technology” expresses the intent of TRIPS not to exclude from patentability any technical inventions, whatever field of technology they belong to, and therefore, in particular, not to exclude programs for computers as mentioned in and excluded under Article 52(2)(c) EPC (T 1173/97, OJ EPO 1999, 609, Reasons, point 2.3).

- The Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC explicitly states that the above considerations on the technical character of inventions apply to the assessment of computer programs.

Non-exhaustive list of “non-inventions”

Article 52(2) EPC contains a non-exhaustive list of “non-inventions”, i.e. subject-matter which is not to be regarded as an invention within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC (Please see ANNEX II: T 154/04, DUNS LICENSING ASSOCIATES, OJ EPO 2008, 46, Reasons, points 6, 8).

Article 52 EPC:

(2) The following in particular shall not be regarded as inventions within the meaning of paragraph 1:

(a) discoveries, scientific theories and mathematical methods;

(b) aesthetic creations;

(c) schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers;

presentations of information.

The list includes “schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers” (Article 52(2)(c) EPC). Even though the “non-inventions” in Article 52(2)(c) EPC cover a broad range of exclusions, they have in common that they refer to activities which do not aim at any direct technical result but are rather of an abstract and intellectual character (T 22/85, OJ EPO 1990, 12, Reasons, point 2).

In other words, based on this list of “non-inventions”, additional conditions have to be fulfilled for patenting software-related inventions compared to inventions in, for example, electrical engineering or mechanical engineering.

Course of EPC 2000 deletion of programs for computers was considered

The negotiations leading up to the EPC 2000 are recorded in travaux préparatoires (= official record of the negotiation). The document „Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC (MR/2/00)“ of the travaux préparatoires forms the most important reference document. The document Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC (MR/2/00) was drawn up by the Administrative Council and addresses the Revision Conference for consideration. The document was issued on October 13, 2000. MR/2/00 is hence – as part of a subsequent agreement between the contracting states concerning the EPC – a valid instrument for construing the Convention according to the traditional rules of interpretation (see decision G 5/83 (supra), Reasons No. 5, rule (4), and the corresponding Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969; T 154/04, Reasons, point 8).

In the year 2007 an adapted version of the European Patent Convention (EPC) entered into force. This new convention is called EPC 2000. The EPC 2000 comprises inter alia amendments regarding Art. 52 EPC whereby this article, as you know, plays a significant role in computer-implemented inventions.

The „Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC (MR/2/00)“ was issued before the final conference of the contracting states to revise the 1973 EPC. In the MR/2/00 the Committee on Patent Law and the Administrative Council has advocated the deletion of programs for computers from Article 52(2)(c) EPC!

Nevertheless, in the final conference of the contracting states to revise the 1973 EPC it was decided that Art. 52(1) EPC has to be amended (introducing the term “all fields of technology”) but Art. 52(2) EPC (list of non-inventions, inter alia “programs for computers”) remains unchanged. The main argument for not deleting the term was that the possible regulation of patent protection for computer programs by EU law (rejected on 6 July 2005 by the European Parliament) should not be anticipated. At the end, the regulation of patent protection for computer programs was rejected on 6 July 2005 by the European Parliament.

Subject-matter or activities “as such”

Article 52(3) EPC limits the exclusion from patentability of the subject-matter and activities referred to in Article 52(2) EPC to “such subject-matter or activities as such”.

Article 52 EPC:

(3) Paragraph 2 shall exclude the patentability of the subject-matter or activities referred to therein only to the extent to which a European patent application or European patent relates to such subject-matter or activities as such.

This limitation is understood as a bar to a broad interpretation of the “non-inventions” listed in Article 52(2) EPC (G 2/12, OJ EPO 2016, A27, Reasons, point VII.2(3)(b), penultimate paragraph, referring to T 154/04, Reasons, point 6).

As soon as in a computer implemented inventions a technical feature is claimed, then it is no longer regarded as a non-invention “as such”. This is called the “any hardware approach”.

In other words, Art. 52(3) EPC provides the possibility to apply for a patent for software-related inventions.

Inventive step

Article 56 EPC gives a negative definition of the “inventive step” required under Article 52(1) EPC, by setting out that an invention shall be considered as involving an inventive step “if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art”. In order to assess inventive step in an objective and predictable manner, the so-called “problem-solution approach” was developed, consisting of the following stages:

(i) determining the “closest prior art”;

(ii) assessing the technical results (or effects) achieved by the claimed invention when compared with the “closest prior art” determined;

(iii) defining the technical problem to be solved, the object of the invention being to achieve said results; and

(iv) considering whether or not the claimed solution, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person (see, for example, Case Law of the Boards of Appeal, 9th ed. 2019, I.D.2).

II. Any Hardware Approach

According to Article 52(2) and (3) EPC, “programs for computers as such” are not an invention. To ensure that the door to a patent for a computer-implemented invention is not closed, there is the “any hardware approach”, which is discussed in this chapter. The information is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 28 to 29.

Avoiding exclusion under Article 52 EPC

- In general, a method involving technical means is an invention within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC.

- This assessment is made without reference to the prior art (T 258/03, Hitachi, OJ EPO 2004, 575, Headnote I and Reasons, points 4.1 to 4.7; T 388/04, OJ EPO 2007, 16, Headnote I; T 1082/13, Reasons, point 1.1).

- This approach has sometimes been described as the “any technical means” or “any hardware” approach (see reference in G 3/08, OJ EPO 2011, 10, Reasons, point 10.6).

According to the established case law, a claim directed to a computer-implemented invention avoids exclusion under Article 52 EPC merely by referring to the use of a computer, a computer-readable storage medium or other technical means (T 697/17, Reasons, point 3.4).

Example:

Claim 1: “A computer-implemented method comprising steps A, B, […]”

Implicitly claimed technical means

A technical feature may be described at a high level of abstraction or functionally, and it may be implicitly evident that a certain claimed method is computer-implemented and hence technical (T 697/17, Reasons, point 3.3 and 3.5).

Example (T 697/17, Reasons, point 3.5):

Claim 1: “Method of updating values in a complex structured type column […] in a relational database system including steps performed by modules of a database system.”

On the other hand, the mere possibility of making use of an unspecified computer for performing a claimed method is not enough to establish the use of technical means for the purposes of Article 52 EPC (T 388/04, Reasons, point 3).

Conclusion

In practice, the feature “computer-implemented” in a claim is sufficient to involve a technical means. Therefore, such a subject matter is considered to be an invention according to Article 52(1) EPC. In other words, the use of the feature “computer-implemented” explicitly or at least implicitly in a computer implemented invention claim results in a computer implemented invention being considered an invention under Art. 52(1) EPC and therefore technical“.

III. COMVIK Approach

A computer implemented invention claim usually has at least one technical feature (to be considered an “invention” under Article 52(1) EPC) and non-technical features from the list of non-inventions under Article 52(2) EPC, e.g. features relating to “programs for computers”. This means that there is usually a mixture of technical and non-technical features in a computer implemented invention claim. The COMVIK approach – discussed in the following chapter – is now used to determine which features in such a computer implemented invention claim can contribute to inventive step. This chapter is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 30 to 34.

Summarized jurisprudence of the boards of appeal regarding subject-matter excluded from patentability

Decision T 154/04 – please see ANNEX II – summarised the jurisprudence of the boards of appeal on the application of Articles 52, 54 and 56 EPC in the context of subject-matter and activities excluded from patentability under Article 52(2) EPC in the following principles (T 154/04, Estimating sales activity/ DUNS LICENSING ASSOCIATES, Reasons, point 5):

(A) Article 52(1) EPC sets out four requirements to be fulfilled by a patentable invention: there must be an invention, and if there is an invention, it must satisfy the requirements of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability.

(B) Having technical character is an implicit requisite of an “invention” within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC (requirement of “technicality”).

(C) Article 52(2) EPC does not exclude from patentability any subject matter or activity having technical character, even if it is related to the items listed in this provision since these items are only excluded “as such” (Article 52(3) EPC).

(D) The four requirements – invention, novelty, inventive step, and susceptibility of industrial application – are essentially separate and independent criteria of patentability, which may give rise to concurrent objections. Novelty, in particular, is not a requisite of an invention within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC, but a separate requirement of patentability.

(E) For examining patentability of an invention in respect of a claim, the claim must be construed to determine the technical features of the invention, i.e. the features which contribute to the technical character of the invention.

(F) It is legitimate to have a mix of technical and “non-technical” features appearing in a claim, in which the non-technical features may even form a dominating part of the claimed subject matter. Novelty and inventive step, however, can be based only on technical features, which thus have to be clearly defined in the claim. Non-technical features, to the extent that they do not interact with the technical subject matter of the claim for solving a technical problem, i.e. non-technical features “as such”, do not provide a technical contribution to the prior art and are thus ignored in assessing novelty and inventive step.

(G) For the purpose of the problem-and-solution approach, the problem must be a technical problem, which the skilled person in the particular technical field might be asked to solve at the relevant priority date. The technical problem may be formulated using an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field, and which is thus not part of the technical contribution provided by the invention to the prior art. This may be done in particular to define a constraint that has to be met (even if the aim stems from an a posteriori knowledge of the invention).

Different types of features

According to principle (F) above it is distinguished between:

- Technical features.

- Non-technical features: Features which, on their own, would be considered “non-inventions” under Article 52(2) EPC (whether such features contribute to the technical character of the invention has to be assessed in the context of the invention as a whole). This definition is from G1/19.

- Non-technical features “as such”: (In addition to the definition re non-technical features mentioned before) they do not interact with the technical subject matter of the claim for solving a technical problem. And/or, they do not provide a technical contribution to the prior art, see T 154/04 above.

Principles (F) and (G) above were established in the COMVIK-decision

The Headnote of the COMVIK-decision (T 641/00) reads as follows:

- An invention consisting of a mixture of technical and non-technical features and having technical character as a whole is to be assessed with respect to the requirement of inventive step by taking account of all those features, which contribute to said technical character whereas features making no such contribution cannot support the presence of inventive step.

- Although the technical problem to be solved should not be formulated to contain pointers to the solution or partially anticipate it, merely because some feature appears in the claim does not automatically exclude it from appearing in the formulation of the problem. In particular where the claim refers to an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field, this aim may legitimately appear in the formulation of the problem as part of the framework of the technical problem that is to be solved, in particular as a constraint that has to be met.

In other words, according to principle 1 all features of the claim (both technical and non-technical features) which contribute to the technical character of the invention are considered for inventive step.

Further explanations to principle 2 are given in the discussion of the decision T 154/04, see ANNEX II.

The principles set out in the principles 1 and 2 above for dealing with non-technical features in the assessment of inventive step for computer-implemented inventions will be referred to in the following as the “COMVIK approach”.

What is the technical character?

Above, the term technical character has appeared in T 154/04 and in the Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC. In summary, the following definitions are used for the term technical character in G1/19:

- an implicit requisite of an “invention” within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC,

- a requirement of “technicality”,

- a “technical teaching”, i.e. an instruction addressed to a skilled person as to how to solve a particular technical problem using particular technical means.

More about features

Features which can be considered to be technical per se do not necessarily contribute to the technical solution of a technical problem. An invention may have

(i) technical features which contribute,

(ii) technical features which do not contribute,

(iii) non-technical features which contribute and

(iv) non-technical features which do not contribute (non-technical features “as such”)

to the technical solution of a technical problem and thereby potentially to the presence or not of an inventive step.

While (i) and (iv) are self-evident, features according to (iii) have been established by the case law described above (principle (F): non-technical features interacting with the technical subject matter of the claim for solving a technical problem).

Case (ii) occurs if features that per se qualify as technical cannot contribute to inventive activity because they have no technical function within the context of the claimed invention, see e.g. below T 619/02 (OJ EPO 2007, 63, Reasons, points 2.2, 2.6.2) concerning perfumes.

Example:

The T619/02 is in regard to a claimed odour selection method in which the resulting odour has not been properly processed or transformed, but merely selected from among a series of existent odours. These features are not excluded by Art. 52(2) and (3) EPC. Nevertheless, the claimed method relies on no more than the perceptional assessment of odours and stimuli for the purpose of evaluating their aesthetic evocation attributes. Since beyond a purely perceptual evocative inducing effect no technical information, i.e. no technical quality or technical significance can be attributed to the selected odour, the result of the claimed method constitutes a non-technical selection. Accordingly, no technical effect is achieved by the claimed method.

In other words, in the mentioned example, the claim features seem at first glance to be excluded according to the non-invention list of Art. 52(2) EPC. However, in the view of the Board, none of the claimed features in the mentioned example is mentioned in this list. Therefore, the features are considered to be technical features. Nevertheless, the technical features have no technical effect and therefore are technical features according to (ii) above which are not considered regarding inventive step.

Even before the COMVIK approach was established, technically non-functional modifications (even if they could per se be considered technical) could be considered irrelevant in the assessment of inventive step (see T 72/95, Reasons, point 5.4).

Why was the COMVIK approach developed?

The COMVIK approach was developed as a means of applying the problem-solution approach to computer-implemented inventions that encompass non-technical features (see principle (F) mentioned above). Subsequent cases noted that the COMVIK approach does not contradict the problem-solution approach; rather, it is a special application of the problem-solution approach to inventions that contain a mix of technical and non-technical features (T 1503/12, Reasons, point 3.3).

Illustration of the COMVIK approach

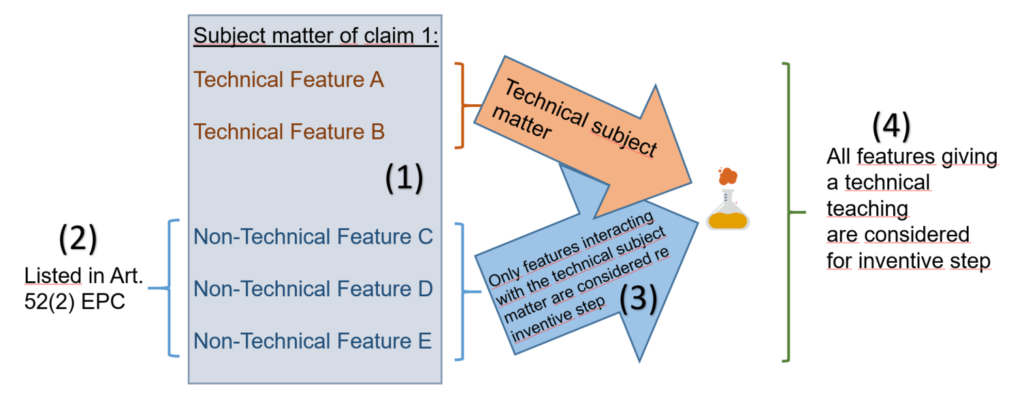

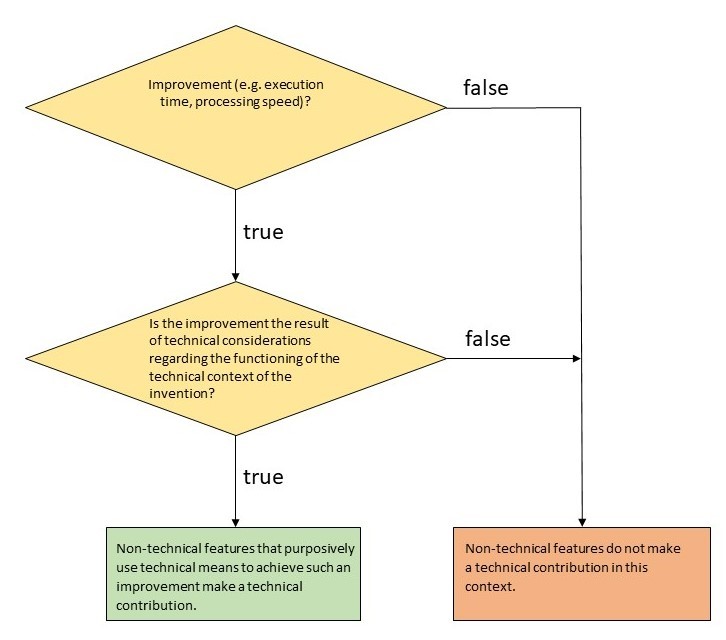

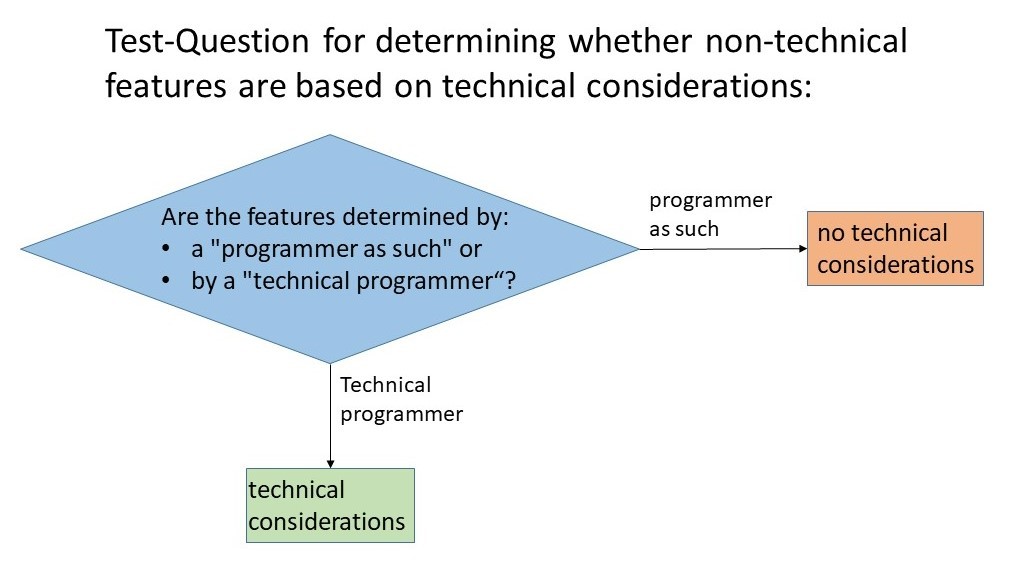

A summary of the COMVIK approach is illustrated in the figure below:

- The blue block (1) in the figure shows a CII claim having technical features and non-technical features. Technical features are e.g. the feature “computer implemented” (please see chapter II “any hardware approach”) and/or “functional data” (please see chapter IV “Potential technical effects”) and/or other technical features.

- Non-technical features are disclosed in the list of Art. 52(2) EPC, marked with (2), e.g. features regarding “programs for computers”.

- According to the COMVIK approach, non-technical features can contribute to the technical character. For this, they have to interact with the technical subject matter of the claim (a technical subject-matter may consist, at least in part, of non-claimed technical features, please see Chapters VIII and IX). This is represented by the two arrows (3) which meet in the conical flask (in which a chemical reaction takes place).

- These non-technical features and the technical features then give technical teaching considered for inventive step, see mark (4) in the figure.

- If the non-technical features do not interact with the technical subject matter, then they are considered to be “non-technical features as such” and they are not taken into account in the inventive step.

Example regarding the application of the COMVIK approach

The following example for the COMVIK approach is based on the “Guidelines for Examination of the EPO” G-VII-5.4.2.5.

Claim 1:

A method for coating a workpiece using a thermal spray coating process, the method comprising:

(a) applying, using a spray jet, a material to the workpiece by thermal spray coating;

(b) monitoring the thermal spray coating process in real time by detecting properties of particles in the spray jet and supplying the properties as actual values;

(c) comparing the actual values with target values;

and, in the event that the actual values deviate from the target values,

(d) adjusting process parameters for the thermal spray coating process automatically by a controller on the basis of a neural network, said controller being a neuro-fuzzy controller which combines a neural-network and fuzzy logic rules and thereby maps statistical relationships between input variables and output variables of the neuro-fuzzy controller.

Background: The invention relates to the control of an industrial process, i.e. thermal spray coating of a workpiece. The material used for the coating is injected with the help of a carrier gas into the high-temperature jet, where it is accelerated and/or molten. The properties of the resulting coatings are subject to great fluctuations, even with seemingly constant parameters of the coating operation. The spray jet is monitored visually with a CCD camera. The image picked up by the camera is sent to an image processing system, from which the properties of particles in the spray jet (e.g. velocity, temperature, size, etc) can be derived. A neuro-fuzzy controller is a mathematical algorithm which combines a neural network with fuzzy-logic rules.

Application of the steps of the problem-solution approach according to COMVIK:

Step (i): The method is directed at thermal spray coating, i.e. a specific technical process, comprising various concrete technical features, e.g. particles, workpiece, a spray coating device (implicit).

Step (ii): Document D1 discloses a method for the control of a thermal spray coating process by applying material to a workpiece using a spray jet, detecting deviations in the properties of the particles in said spray jet and adjusting process parameters automatically on the basis of the outcome of a neural network analysis. This document represents the closest prior art.

Step (iii): The difference between the method of claim 1 and D1 concerns the use of a neuro-fuzzy controller combining a neural network and fuzzy logic rules as specified in the second part of step (d).

Computational models and algorithms related to artificial intelligence are, on their own, of an abstract mathematical nature. The feature of combining results of a neural network analysis and fuzzy logic defines a mathematical method when taken on its own. However, together with the feature of adjusting the process parameters, it contributes to the control of the coating process. Hence, the output of the mathematical method is directly used in the control of a specific technical process.

Control of a specific technical process is a technical application. In conclusion, the differentiating feature contributes to producing a technical effect serving a technical purpose and thereby contributes to the technical character of the invention. Therefore, it is taken into account in the assessment of inventive step.

Defining the object of the invention using aim of non-technical features as such (COMVIK decision Headnote No. 2)

In the previous chapters we discussed Headnote 1 of COMVIK T 641/00 regarding mixed inventions having technical and non-technical features. Below you will find information about Headnote 2 (which you will find above) of COMVIK T 641/00. Headnote 2 deals with the formulation of the subject-matter of mixed-type inventions. Below you will find explanations based on decision T 154/04 Estimation of sales activity/DUNS LICENSING ASSOCIATES, reasons point 16:

For the purpose of the problem-and-solution approach developed as a test for whether an invention meets the requirement of inventive step, the problem must be a technical problem (see the COMVIK decision T 641/00 (supra), Reasons Nos. 5 ff.). The definition of the technical problem, however, is difficult if the actual novel and creative concept making up the core of the claimed invention resides in the realm outside any technological field, as it is frequently the case with computer-implemented inventions. Defining the problem without referring to this non-technical part of the invention, if at all possible, will generally result either in an unintelligible vestigial definition, or in an contrived statement that does not adequately reflect the real technical contribution provided to the prior art.

The Board, therefore, allowed in COMVIK an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field to appear in the formulation of the problem as part of the framework of the technical problem that is to be solved, in particular as a constraint that is to be met (Reasons No. 7). Such a formulation has the additional, desirable effect that the non-technical aspects of the claimed invention, which generally relate to nonpatentable desiderata, ideas and concepts and belong to the phase preceding any invention, are automatically cut out of the assessment of inventive step and cannot be mistaken for technical features positively contributing to inventive step. Since only technical features and aspects of the claimed invention should be taken into account in assessing inventive step, i.e. the innovation must be on the technical side, not in a non-patentable field (see also decisions T 531/03 – Discount certificates/CATALINA (not published in OJ EPO) Reasons Nos. 2 ff., and T 619/02 (supra), Reasons No. 4.2.2), it is irrelevant whether such a non-technical aim was known before the priority date of the application, or not.

Example re defining the object of the invention using aim of non-technical features as such (COMVIK decision Headnote No. 2)

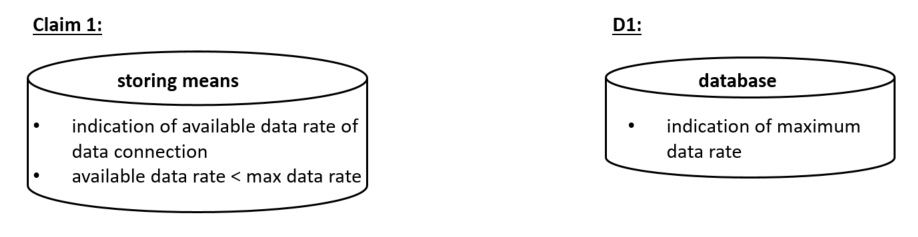

The following example for the COMVIK approach is based on the “Guidelines for Examination of the EPO” G-VII-5.4.2.3.

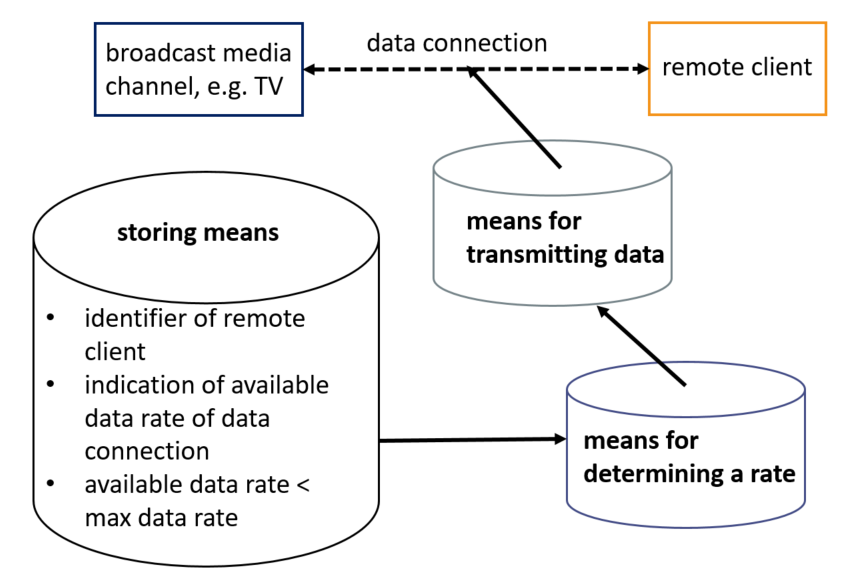

Claim 1:

A system for the transmission of a broadcast media channel to a remote client over a data connection, said system including:

(a) means for storing an identifier of the remote client and an indication of an available data rate of the data connection to the remote client, said available data rate being lower than the maximum data rate for the data connection to the remote client;

(b) means for determining a rate at which data is to be transmitted based on the indication of the available data rate of the data connection; and

(c) means for transmitting data at the determined rate to said remote client.

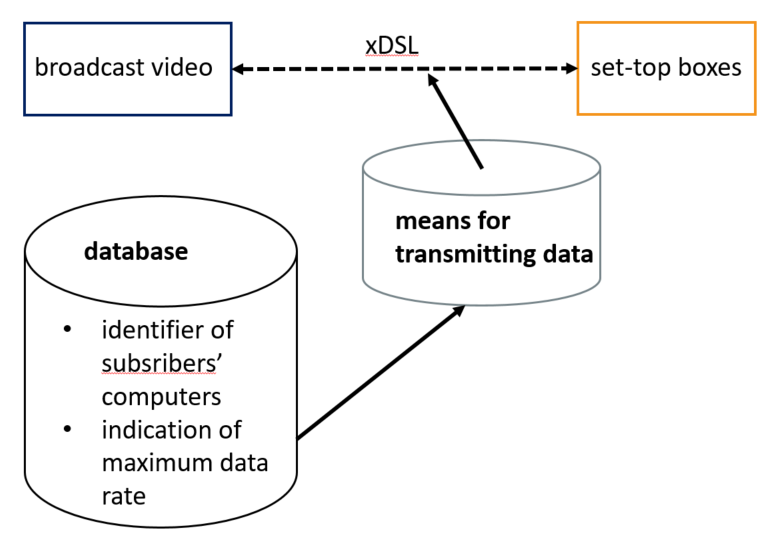

Document D1, which discloses in the figure below a system for broadcasting video over an xDSL connection to the set-top boxes of subscribers, is selected as the closest prior art. The system comprises a database storing identifiers of subscribers’ computers and, in association with them, an indication of the maximum data rate for the data connection to each subscriber’s computer. The system further comprises means for transmitting the video to a subscriber’s computer at the maximum data rate stored for said computer.

The differences between the subject-matter of claim 1 and D1 are:

(1) Storing an indication of an available data rate of the data connection to the remote client, said available data rate being lower than the maximum data rate for the data connection to the remote client.

(2) Using said available data rate to determine the rate at which the data is transmitted to the remote client (instead of transmitting the data at the maximum data rate stored for said remote client as in D1).

The purpose served by using an “available data rate” which is lower than a maximum data rate for the data connection to the remote client is not apparent from the claim. Therefore, the relevant disclosure in the description is taken into account. In the description, it is explained that a pricing model is provided which allows a customer to choose from several service levels, each service level corresponding to an available data-rate option having a different price. A user may select an available data rate lower than the maximum data rate possible with the connection in order to pay less. Hence, using an available data rate which is lower than the maximum data rate for the connection to the remote client addresses the aim of allowing a customer to choose a data-rate service level according to that pricing model. This is not a technical aim, but an aim of a financial, administrative or commercial nature and thus falls under the exclusion of schemes, rules and methods for doing business in Art. 52(2)(c). It may thus be included in the formulation of the objective technical problem as a constraint to be met.

The features of storing the available data rate and of using it to determine the rate at which the data is transmitted have the technical effect of implementing this non-technical aim.

The objective technical problem is therefore formulated as how to implement in the system of D1 a pricing model which allows the customer to choose a data-rate service level.

IV. Two-hurdle Approach

In order to be patentable, an invention must pass the eligibility test under Article 52 EPC (i.e. it must not be one of the “non-inventions” referred to therein) and must also satisfy the other criteria listed in that Article (novelty, inventive step, etc.). For computer-implemented inventions, the twofold test for patent eligibility and for inventive step (using the COMVIK criteria) is often referred to as the “two-hurdle approach”, which will be discussed below on the basis of decision G1/19 of the Enlarged Board of Appeal, points 37 to 39.

The first hurdle is easier to overcome

It may be that a shift has taken place in the relative level of each of these two hurdles in the sense that it has become easier to clear the eligibility hurdle of Article 52 EPC and more difficult to pass the inventive step hurdle of Article 56 EPC. As result of this shift, it could be said that there is now in effect an additional intermediate step to assess the “eligibility of the feature to contribute to inventive step”.

The two-hurdle approach for computer-implemented inventions actually entails three steps:

(i) assessing the invention’s eligibility under Article 52 EPC,

(ii) establishing whether a feature contributes to the technical character of the invention as an intermediate step,

(iii) assessing whether the invention is based on an inventive step vis-à-vis the closest prior art.

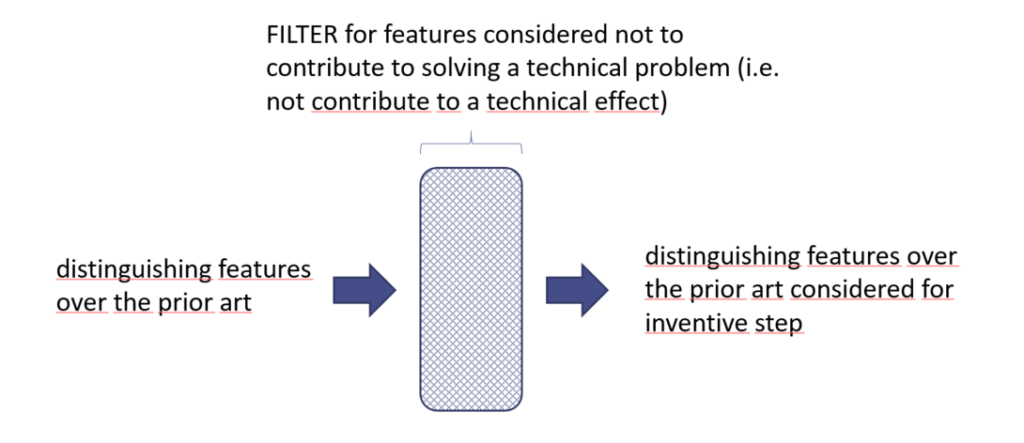

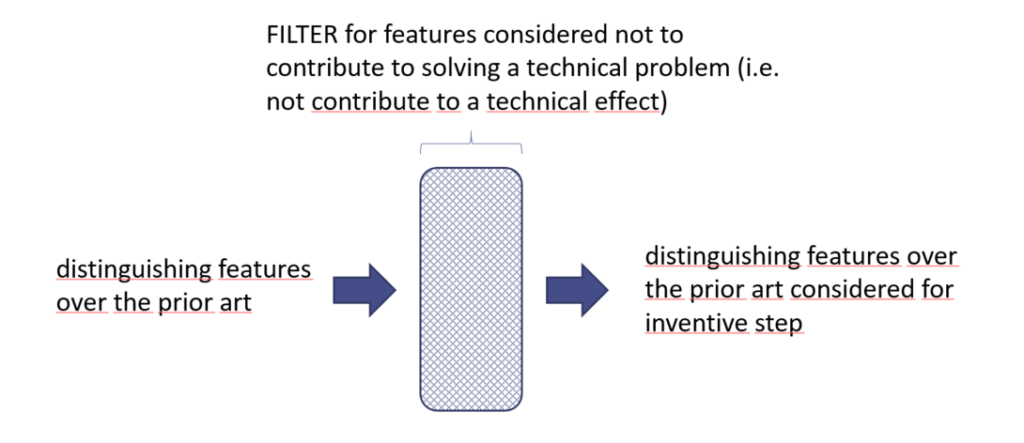

Filter for features contributing to the technical character

This additional intermediate step serves as a filter for features contributing to a technical solution of a technical problem in view of the closest prior art. Only those distinguishing features can contribute to inventive step, see figure below.

V. What is technical?

The German Federal Court of Justice defined the term “technical teaching” in the 1960s, with which the Court agrees in G1/19. The technical teaching is implied in the term “invention”. The following chapter gives a brief overview of the above-mentioned definition and builds a bridge to data regarding technicality, which is an essential part of computer-implemented inventions. This information is based on the decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal G1/19, points 75 to 77.

Red dove decision

The EPC, like national patent laws, does not define “invention” or “technical”. However, from Article 52 EPC, it can be concluded that only “technical” inventions are patentable (“in all fields of technology”, see also G 2/07, OJ EPO 2012, 130, Reasons, point 6.4.2.1).

In G 2/07, which concerned a referral in the field of biotechnology, the Enlarged Board cited the definition of an invention given by the German Federal Court of Justice (“Bundesgerichtshof”) in the latter’s “Rote Taube” decision of 27 March 1969 (Case X ZB 15/67). According to this decision, the term “invention” implied a technical teaching, characterised as

“a teaching to methodically utilize controllable natural forces to achieve a causal, perceivable result” (“eine Lehre zum planmässigen Handeln unter Einsatz beherrschbarer Naturkräfte zur Erreichung eines kausal übersehbaren Erfolgs”),

see the German original in GRUR 1969, 672, point 3, and the English translation published in 1 IIC (1970), 136).

EBoA refrains from putting forward a definition for “technical”

In G 2/07, the Enlarged Board held that this standard “still holds good today and can be said to be in conformity with the concept of ‘invention’ within the meaning of the EPC” (G 2/07, Reasons, point 6.4.2.1, fourth paragraph). The “Rote Taube” decision predates the non-exhaustive list of exclusions from patentability in Article 52(2) EPC. However, the Enlarged Board, when referring to “Rote Taube”, must have considered that the negative definition resulting from the list of exclusions in the EPC did not contradict the findings in “Rote Taube”. In accordance with its earlier case law and with the approach chosen by the legislator, the Enlarged Board in G1/19 refrains from putting forward a definition for “technical”.

Cognitive content of data

It is generally recognised in the case law of the boards of appeal that the cognitive content of data is not technical in nature (see e.g. T 1000/09, Reasons, point 7). The idea of treating information as part of the concept of “forces of nature” did not take root (see Zech in “Methodenfragen des Patentrechts” (Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2018, 137, 140)). The fact that the list of “non-inventions” in Article 52(2) EPC was discussed but not changed in the course of the EPC 2000 revision project supports the position that the term “technical” must remain open, not least in anticipation of potential new developments.

VI. Technicality of Computer-Implemented Inventions using the two-hurdle Approach

This chapter examines the two-hurdle approach in more detail, wherein this information is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 78 to 84.

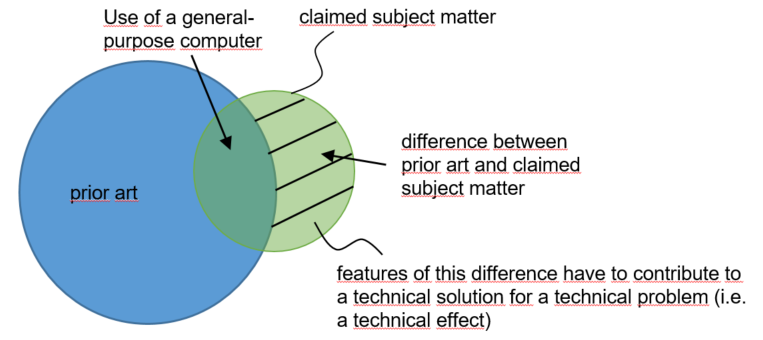

First and second hurdle

Patent eligibility, the first hurdle, is to be assessed under Article 52 EPC without considering the prior art, i.e. without regard to whether computers existed at the priority date of the invention. The use of a computer in the claimed subject-matter therefore makes it eligible under Article 52 EPC.

For the second hurdle, the prior art is to be considered. Inventive step is based on the difference between the prior art and the claimed subject-matter, please see figure below.

The requirement that the features supporting inventive step contribute to a technical solution for a technical problem means that the invention, understood as a teaching based on existing prior art, has to be a “technical invention”. The use of a general-purpose computer always constitutes prior art in this context, please see figure above.

Hence, the invention to be assessed under this provision needs to be “technical” beyond the use of a general-purpose computer. For this assessment, the definition of a technical invention in Article 52 EPC, in particular the list of “non-inventions” in Article 52(2) EPC, can be useful for determining whether specific features contribute to inventive step (see G 3/08, Reasons, point 10.13.1).

Technical features per se may not contribute to inventive step

In general terms, features that can be considered technical per se may still not contribute to inventive step if they do not contribute to the solution of a technical problem, please see also the example in chapter III. “COMVIK approach”. In line with this principle, a technical step within a computer-implemented process may or may not contribute to the problem solved by the invention.

Example:

In case T 1670/07, the claim was directed to a “method of facilitating shopping with a mobile wireless communications device to obtain a plurality of purchased goods (…) from a group of vendors located at a shopping location”. The board found that the intrinsic technical nature of a computer-based implementation was not enough to make the whole process technical since the “selection of vendors” presented to the user in the course of the claimed method was not a technical effect, and the transmission of the selection no more than the dissemination of information (Reasons, point 9).

While Article 52 EPC is taken as the framework for determining whether there is a technical invention, the COMVIK approach applies the same criteria in the examinations whether the claimed subject-matter fulfils the provisions of Article 52 EPC and whether any distinguishing features may be considered for the analysis under Article 56 EPC. If, for the inventive step analysis, only those differences from the prior art are to be considered which contribute to solving a technical problem, then this requirement serves as a filter through which the features distinguishing an invention from the prior art must first pass, please see figure below.

Specific effect has to be achieved over the whole scope of the claim

It is a general principle that the question whether a feature contributes to the technical character of the claimed subject-matter is to be assessed in view of the whole scope of the claim.

Using the problem-solution approach, the analysis under Article 56 EPC may reveal that a specific problem is not solved (i.e. a specific effect is not achieved) over the whole scope of the claim. In such cases, the aforementioned specific problem may not be considered as the basis for the inventive step analysis unless the claim is limited in such a way that substantially all embodiments encompassed by it show the desired effect (see, for example, T 939/92, OJ EPO 1996, 309, Reasons, point 2.6, where the board was not satisfied that substantially all claimed chemical compounds were likely to be herbicidally active). Such limitation is typically achieved by narrowing one or more features (e.g. a temperature or concentration range within a chemical process) and/or by adding one or more limiting features. The above principle, as it was elaborated in the often-cited decision T 939/92, just specifies the further general principle that the entire or substantially the entire claimed subject-matter must fulfil the patentability requirements.

Likewise, a computer-implemented invention may have technical character and a feature may contribute to the technical character of the invention with respect to only parts of the claimed subject-matter.

Example:

An increased speed for an inventive data transmission method (constituting the technical effect) can only be achieved if the size of transmitted data packets exceeds a certain minimum size. In such a case, it may be necessary to limit the size of the data packets accordingly in the corresponding claim feature. Otherwise, there will be possible embodiments falling under the claimed subject matter which achive the effect of increased speed (embodiments having the data packets exceeding the certain minimum size) and possible embodiments falling under the claimed subject matter which do not achieve the effect of an increased speed (embodiments in which the data packets do not exceed the specified minimum size).

The limitation of the claimed subject-matter to a scope for which a technical effect may be acknowledged can be achieved by adding further limiting features, such as steps establishing an interaction with external physical reality.

Claimed invention has to be technical over the whole scope of the claim

Following the COMVIK approach, a feature is only considered for inventive step if and to the extent that it contributes to the technical character of the claimed subject-matter. A pre-requisite for meeting the requirement that the claimed invention is inventive over the whole scope of the claim is that it is also technical over the whole scope. Consequently, the requirement is not met if the claimed feature in question contributes to the technical character only for certain specific embodiments of the claimed invention, see example above.

VII. Aspects of Technicality of Computer-Implemented Inventions

In chapter “III COMVIK approach” we saw that there must be a technical interaction between non-technical features and the technical subject matter of the claim for the non-technical features to be considered for inventive step. Now we will discuss what kind of technical interactions are possible in computer-implemented inventions, basing this chapter on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 85 to 86.

Technical interactions in computer implemented inventions

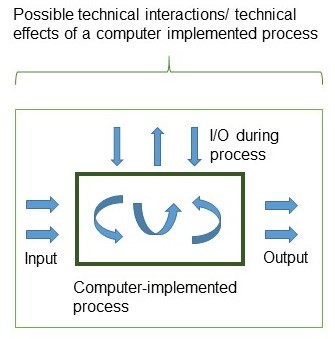

The below figure shows – in a simplified, non-exhaustive form – how and when “technical effects” or “technical interactions” may occur in the context of a computer-implemented process.

The arrows in the figure above represent interactions that are different from abstract data input, data output or internal data processing or transfer. This means, the shown arrows do not represent abstract data.

Features that may contribute to inventive step

Technical input may consist of a measurement; technical output may exist as a control signal used for controlling a machine. Both technical input and technical output are typically achieved through direct links with physical reality. Adaptations to the computer or its operation, which result in technical effects (e.g. better use of storage capacity or bandwidth), are also examples of features that may contribute to inventive step. You can find a a list of examples and references to the relevant board decisions in ANNEX III: T 697/17, Reasons, point 5.2.5.

In sum, technical effects can occur within the computer-implemented process (e.g. by specific adaptations of the computer or of data transfer or storage mechanisms) and at the input and output of this process. Input and output may occur not only at the beginning and the end of a computer-implemented process but also during its execution (e.g. by receiving periodic measurement data and/or continuously sending control signals to a technical system).

Certain features can be technical or non-technical per se

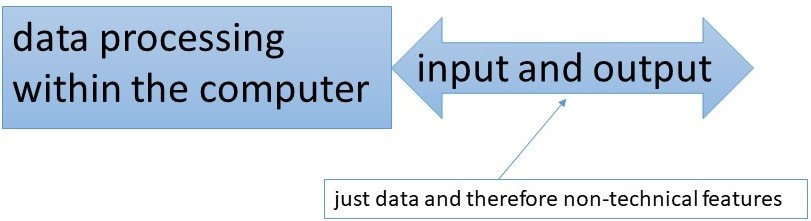

It is self-evident that the input and output are always nothing other than data, if only the data processing within the computer is considered, see figure below.

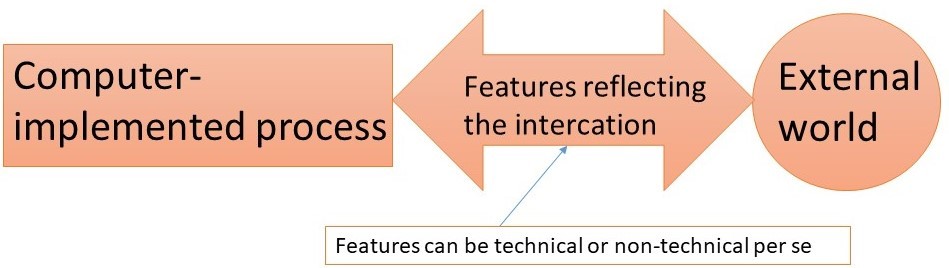

Computer-implemented processes, however, often include features – which could be technical or non-technical per se – that reflect the interaction of the computer with the external world, see figure below.

As explained above, it is not possible to exhaustively describe (or represent in graphical form) every type of feature of a computer-implemented invention that may contribute to the invention’s technical character.

VIII. Direct link to physical reality

A direct link between the claimed subject-matter and (external) physical reality is not necessary in every case, as will be shown below. This chapter is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 87 to 88.

Direct link to physical reality

The decision T 0489/14 (Reasons, point 31), starting from G 3/08, discussed whether a claimed feature must cause a technical effect on a physical entity in the real world in order to contribute to the technical character of the claim. In G 3/08, this question was found to be inadmissible pursuant to Article 112(1)(b) EPC because it could not be established that two boards of appeal had given differing decisions on this issue. Quoting decisions beyond those considered in G 3/08, the board in T 0489/14 identified cases apparently requiring a technical effect directly linked to physical reality, but also others which suggested that a potential technical effect, i.e. an effect achieved only in combination with non-claimed features, was taken into account (Reasons, points 36 and 37).

Following existing case law and taking into account the relevant legal provisions, the Enlarged Board in G1/19 does not see a need to require a direct link with (external) physical reality in every case:

- On the one hand, technical contributions may also be established by features within the computer system used.

- On the other hand, there are many examples in which potential technical effects – which may be distinguished from direct technical effects on physical reality – have been considered in the course of the technicality / inventive step analysis.

A direct link with physical reality is usually sufficient regarding technicality

While a direct link with physical reality, based on features that per se are technical and/or non-technical, is in most cases sufficient to establish technicality, it cannot be a necessary condition, if only because the notion of technicality needs to remain open.

Background: “Direct link” means that features of the physical reality are claimed which cause the technical effect..

IX. Potential Technical Effects

The previous chapter VII “Aspects of technicality of computer-implemented inventions” considered possible interactions between non-technical features and technical features in computer implemented inventions. This chapter discusses, inter alia, possible output interactions and interactions occurring within the computer. The question of whether data based on them can have a technical character and therefore be considered for inventive step is clarified. This information is based on the EBoA decision G1/19, points 89 to 96.

Interactions in computer implemented inventions

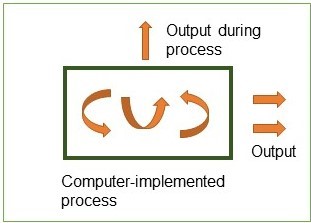

The figure below illustrates that this chapter deals mainly with interactions/ technical effects regarding technical output and adaptations to the computer or its operation (following the figure in chapter VII regarding the interactions).

Such interactions/technical effects play a significant role in inventive step, see also chapter III COMVIK approach.

Potential effects of a computer program

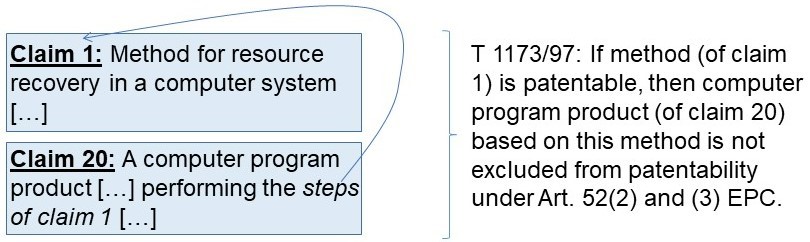

Some of the amicus curiae briefs in G1/19 cited decision T 1173/97 – please see ANNEX IV – in support of the argument that it is sufficient for a computer-implemented invention to have the potential to produce a technical effect. That decision acknowledged that a computer program product may have the potential to cause a predetermined further technical effect, i.e. a technical effect going beyond the technical effects within the computer that necessarily occur when a program is run on a computer (Reasons, points 6 and 7). The claims underlying this decision included claims to a “computer program product directly loadable into the internal memory of a digital computer” and to a “computer program product stored on a computer usable medium”. The only question to be decided was whether these claims were excluded from patentability under Article 52(2) and (3) EPC (Reasons, point 9.1). In that context the board found that, since any (technical or non-technical) effect of a computer program can only be achieved when the program is run on a computer, a program only possesses the “potential” to produce any effect (Reasons, point 9.4). Nonetheless, the board found that “[a] computer program product which (implicitly) comprises all the features of a patentable method” is “in principle considered as not being excluded from patentability under Article 52(2) and (3) EPC” (Reasons, point 9.6).

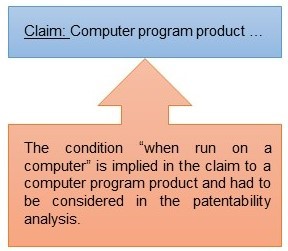

Software is treated as software running on a computer

The acknowledgment of a “potential” to produce an effect in T 1173/97 meant that the effect of a computer program when run on a computer had to be considered in the patentability analysis, or, in other words, that the condition “when run on a computer” was implied in the claim to a computer program product. Based on this conclusion, the case was remitted to the department of first instance for further prosecution, “in particular for examination of whether the wording of the present claims avoids exclusion from patentability under Article 52(2) and (3) EPC” (point 2 of the order).

The T 1173/97 did not address the question whether the claimed invention had technical character, but it made clear that the physical modifications deriving from the execution of the instructions given by the program could not per se constitute the technical character of the invention (Reasons, point 6.6).

Potential further technical effect

The principle developed in T 1173/97 that software (which in itself may only have “potential effects”) is treated as software running on a computer is still applied, while the further analysis (i.e. whether the software causes further technical effects) is now carried out according to the COMVIK approach.

When run on a computer, the combination of the claimed features must establish a technical invention. In the COMVIK analysis, the features have to be assessed as to their contribution to the technical character of the invention.

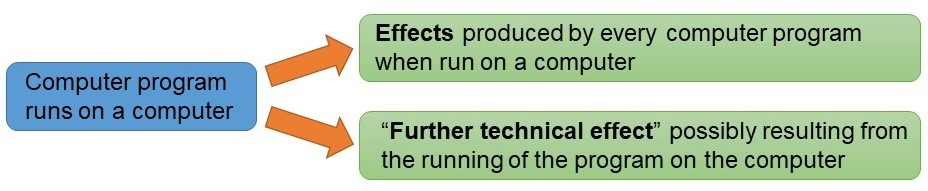

Decision T 1173/97 did distinguish between the effects produced by every computer program when run on a computer and the “further technical effect” possibly resulting from the running of the program on the computer (Reasons, point 9.4).

Of course, such “further technical effect” too may only be achieved when the program is running on the computer, i.e. the program may have the potential to cause such further technical effects which thus could be referred to as “potential further technical effects”.

Background: In the case of a genuine computer program claim, the physical changes occurring in the hardware when the program instructions are executed cannot per se establish technical character. This is because technical character cannot be derived solely from the features common to all computer programs. Otherwise, the prohibition of patenting would become completely meaningless. The technicality of the subject matter of a genuine computer program claim thus presupposes that the underlying teaching goes beyond the normal physical interaction of program and computer, see T 1173/97.

“Potential” technical effects always treated as “real” technical effects?

However, T 1173/97 did not establish whether the claimed computer program was related to any further technical effect but only made clear that a computer program product is not inevitably excluded from patentability (Reasons, point 12.2). In particular, the decision does not imply that, once the software is running on a computer, “potential” technical effects can always be treated as “real” technical effects for the purposes of the analysis according to the COMVIK approach.

This means, the T 1173/97 does not teach that potential further technical effects are considered regarding the COMVIK approach. The decision left this open.

Potential technical effect is an effect achieved in combination with non-claimed features

The decision T 0489/14 – referring decision of G1/19 – cites other decisions which have suggested “that a potential technical effect, i.e. an effect achieved only in combination with non-claimed features, can be taken into account in assessing inventive step” (Reasons, point 37).

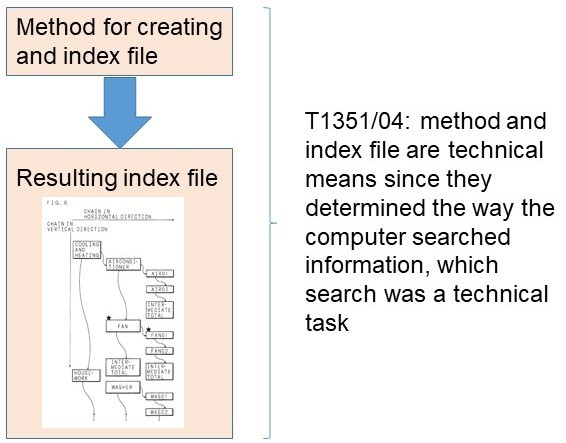

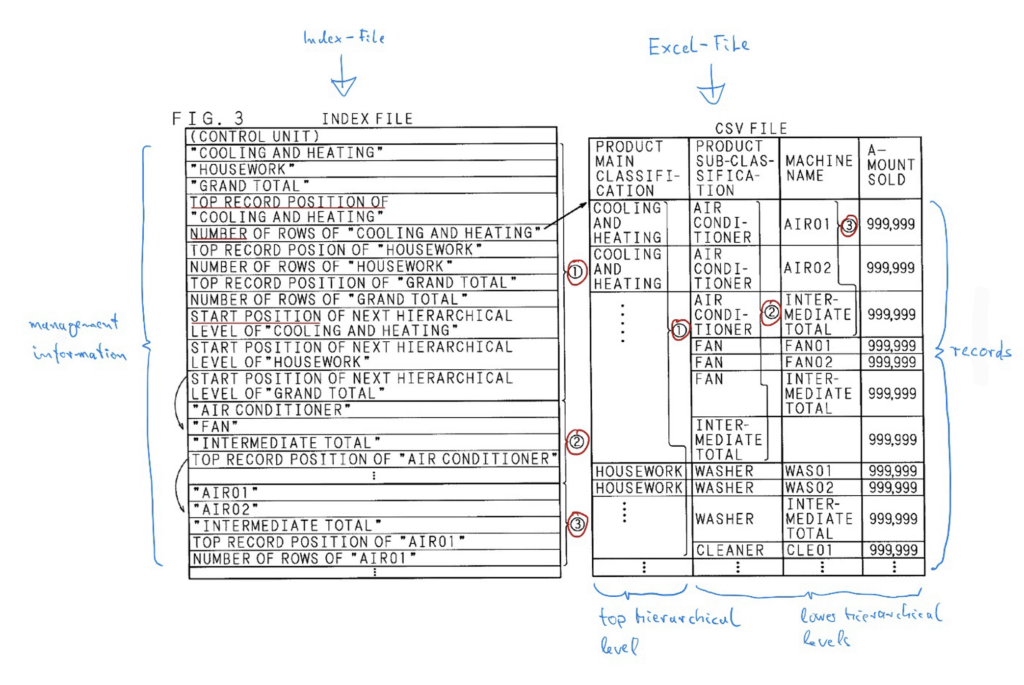

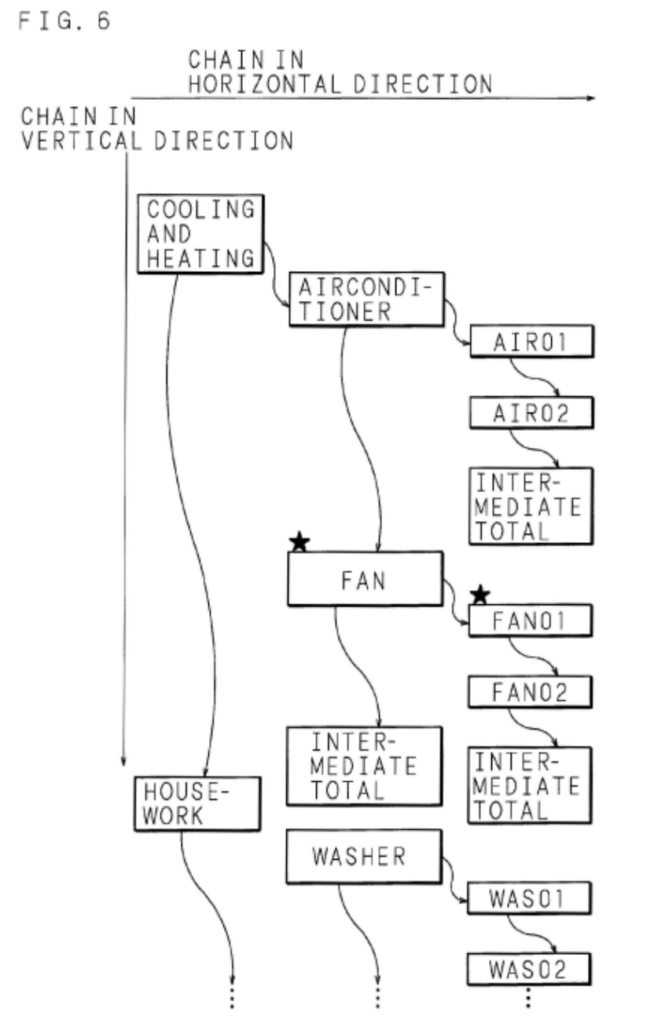

Example (please see also ANNEX V):

In T 1351/04 – in the context of the COMVIK approach – a method for creating an index file and the resulting index file were considered to be technical means, since they determined the way the computer searched information, which search was a technical task (T 1351/04, Catchword and Reasons, point 7), see figure below. In other words: An index file containing management information to be used for searching a file – e.g. an Excel csv-file – and the method for producing the index file are technical means when they determine the way the computer searches information, which is a technical task. The management information e.g. includes starting positions of records in the csv-file.

This decision T 1351/04 (ANNEX V) referred to “functional data, intended for controlling a technical device”, which were “normally regarded as having technical character” (Reasons, point 7.2).

Further example: In T 110/90 (OJ EPO 1994, 557) the subject matter concerns control signals for a printer, which were considered technical features of the text-processing system in which they occurred (see Reasons, point 4).

Data intended for controlling a technical device

The appellant in G1/19 and the President of the EPO, and others too, referred to decision T 208/84 (VICOM, OJ EPO 1987, 14) – see ANNEX VI – as another example of data processing being considered to have a technical effect. This case distinguished a method of digitally processing images from a mathematical method as such (Reasons, points 5 and 6).

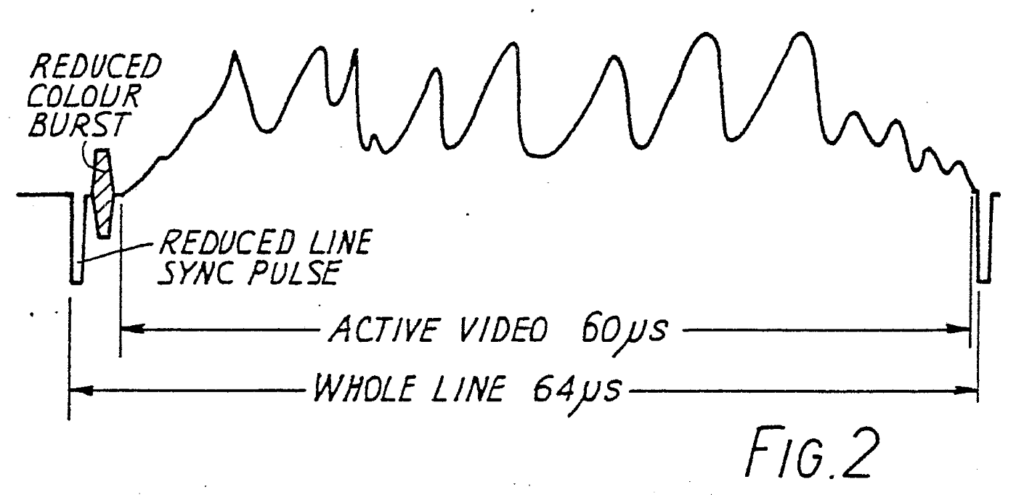

Here, T 163/85 (OJ EPO 1990, 379) can also be mentioned, please see ANNEX VII. It concerned claims to a colour television signal adapted to generate a picture on specific television receivers. The deciding board found that the TV signal as claimed inherently comprised the technical features of the TV system in which it was being used (Reasons, point 2).

Data intended for controlling a technical device may have technical character

The older case law referred to above appears to confirm that data intended for controlling a technical device may be considered to have technical character because it has the potential to cause technical effects.

In the context of the problem-solution approach and the COMVIK approach, such potential technical effects may be considered if the data resulting from a claimed process is specifically adapted for the purposes of its intended technical use. In such cases:

- either the technical effect that would result from the intended use of the data could be considered “implied” by the claim, or

- the intended use of the data (i.e. the use in connection with a technical device) could be considered to extend across substantially the whole scope of the claimed data processing method.

Data should not have relevant uses other than the use with a technical device

On the other hand, the arguments mentioned in the last paragraph cannot be made if claimed data or data resulting from a claimed process has relevant uses other than the use with a technical device (such as for controlling a technical device). In this case, the analysis under Article 56 EPC may reveal that a technical effect is not achieved over substantially the whole scope of the claimed invention (see also chapter VI).

Downstream effects

In the Enlarged Board’s view, the above-mentioned potential technical effects (which may be considered to be technical effects subject to certain conditions) have to be distinguished from the potential effects discussed in T 1173/97. The latter include all (technical and non-technical) effects resulting directly from the running of a program on a computer, i.e. effects occurring within the computer and relating to the hardware which executes the program. By contrast, the former are “downstream” effects which may or may not be caused by said data output.

Of course, numerical data output from a computer is a necessary pre-condition for any effects that are caused, and the “downstream effects” can be seen as a potential effect of the software.

However, the necessarily technical nature of some effects inside the computer does not mean that the “downstream” effects caused by the data output of the computer are necessarily of a technical nature. In T 1173/97 such effects – if considered as technical – were referred to as “further technical effects” (see Reasons, point 9.4).

Conclusions

According to T1173/97 the condition “when run on a computer” was implied in the claim to a computer program product. Furthermore, T1173/97 teaches that a computer program product is not inevitably excluded from patentability.

Further, in this chapter, information regarding a potential technical effect have been given. A potential technical effect is an effect achieved only in combination with non-claimed features. A potential technical effect can be taken into account in assessing inventive step and the COMVIK approach if the data resulting from a claimed process is specifically adapted for the purposes of its intended technical use.

Furthermore, we learnt in this chapter, that functional data is data intended for controlling a technical device. Functional data may be considered to have technical character because it has the potential to cause (further) technical effects and can therefore be considered as a technical feature/ technical means. The (further) technical effect that would result from the intended use of the functional data could be considered “implied” by the claim. Therefore, output-data intended for controlling a technical device may be considered to have technical character.

X. Virtual or Calculated Technical Effects

This chapter discusses whether virtual effects, such as those occuring in a digital twin, can be considered as potential technical effects. This chapter is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 97 to 99.

Technical effects which are not achieved through an interaction with physical reality

It was argued during the referral proceedings of G1/19 that technical effects which are not achieved through an interaction with physical reality, but are calculated in such a way as to correspond closely to “real” technical effects or physical entities, should be treated as technical effects for the purposes of the COMVIK approach. In the Enlarged Board’s view, virtual or calculated technical effects should be distinguished from potential technical effects which, for example when a computer program or a control signal for an image display device is put to its intended use, necessarily become real technical effects.

Calculated status information

Calculated status information or physical properties concerning a physical object are information which may reflect properties possibly occurring in the real world. However, first and foremost, they are mere data which can be used in many different ways. There may exist exceptional cases in which such information has an implied technical use that can be the basis for an implied technical effect.

Still, in general, data about a calculated technical effect is just data, which may be used, for example, to gain scientific knowledge about a technical or natural system, to take informed decisions on protective measures or even to achieve a technical effect. The broad scope of a claim concerning the calculation of technical information with no limitation to specific technical uses would therefore routinely raise concerns with respect to the principle that the claimed subject-matter has to be a technical invention over substantially the whole scope of the claims (see chapter VI, referring to T 939/92).

Example of calculated status information or physical properties concerning a physical object implies technical use that can be the basis for an implied technical effect

The calculation of the physical state of an object (e.g. its temperature) is typically part of a measurement method. It is generally acknowledged that measurements have technical character since they are based on an interaction with physical reality at the outset of the measurement method.

Measurements are often carried out using indirect measurements, for example, the measurement of a specific physical entity at a specific location by means of measurements of another physical entity and/or measurements at another location (see e.g. T 91/10, Reasons, point 5.2.1; T 1148/00, Reasons, point 9). Even though such indirect measurements may involve significant computing efforts, they are still related to physical reality and thus of a technical nature, regardless of what use is made of the results (for a combination of measurements and simulations see e.g. T 438/14).

Following chapter VII “Aspects of technicality in computer-implemented inventions”, the above explanation is thus an input-side interaction, see figure below.

Conclusions

- A virtual technical effect is calculated in such a way as to correspond closely to “real” technical effects or physical entities.

- Potential technical effects which, for example when a computer program or a control signal for an image display device is put to its intended use, necessarily become real technical effects.

- Calculated status information or physical properties concerning a physical object are mere data which can be used in many different ways.

- In general, data about a calculated technical effect is just data.

- The calculation of the physical state of an object (e.g. its temperature) is typically part of a measurement method. It is generally acknowledged that measurements have technical character.

XI. Criterion of a “Tangible Effect”

This chapter deals with the question of whether an effect is a requirement for patentability. The information is based on the Enlarged Board of Appeal decision G1/19, points 100 to 101.

Pulse sequences could be likened to control signals having potential further technical effects when put to their intended use

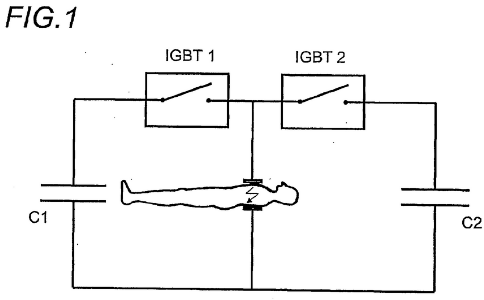

In support of the technical nature of calculated (technical) data, it was argued by the President of the EPO in the case G1/19 that the case law of the boards of appeal does not require a “tangible effect” for an invention to be patentable. The representatives of the President of the EPO referred in particular to T 533/09. This decision held claims to a defibrillation pulse sequence (see patent 11) to be allowable.

Defibrillation pulses are electric shocks delivered by a defibrillation device to a patient (see paragraph [0069] and Fig. 1 above of said patent). In the context of Article 57 EPC (industrial applicability), the board in T 533/09 held that the notion of a patentable invention was not linked to a “caractère tangible, au sens de matériel” (Reasons, point 7.2). Referring to the travaux préparatoires, the board found that the EPC did not limit patentability to certain categories of inventions (e.g. products and processes).

The decision emphasised the difference from U.S. law, which, unlike the EPC, limited patentable inventions to “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter” under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (Reasons, point 7.2). Even though T 533/09 was not limited to computer-implemented inventions, the claimed pulse sequences could be likened to control signals having potential further technical effects when put to their intended use (see chapter IX “Potential technical effect”, in particular with respect to T 163/85 – colour television signal).

Tangible effect is not a requirement under the EPC

Many cases referring to “tangible” effects use their absence as an argument against patentability (see, as a recent example, T 215/13, Reasons, points 5 and 6 – no tangible technical problem solved). However, the Enlarged Board fully supports the view expressed in T 533/09 (Reasons, point 7.2) that a tangible effect is not a requirement under the EPC.

Moreover, it is unclear to what extent the notions of “tangible effect” and “further technical effect” overlap. A criterion based on tangibility – in addition to the requirement of technicality – thus cannot contribute to a more precise delimitation of patentable inventions.

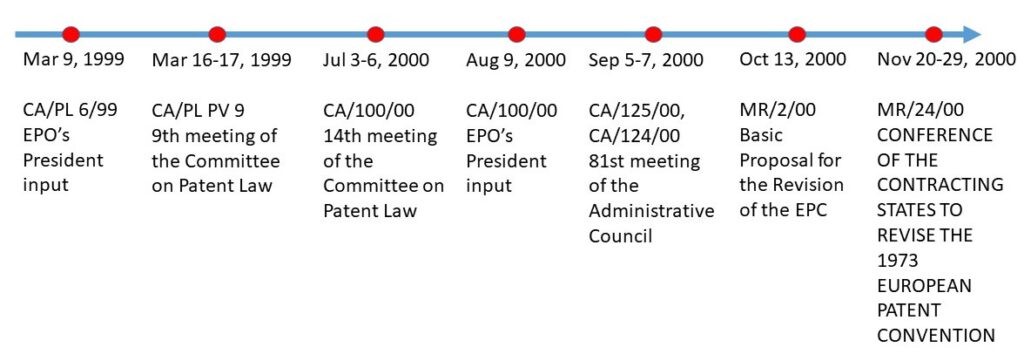

ANNEX I. Travaux préparatoires for the EPC 2000

In the year 2007 an adapted version of the European Patent Convention (EPC) entered into force. This new Convention is known as the EPC 2000. The EPC 2000 includes, among other things, amendments to Art. 52 EPC, which, as you know, plays an important role in computer-implemented inventions. In the end Art. 52(1) EPC was amended (introduction of the term “all fields of technology”) but Art. 52(2) EPC (list of non-inventions, inter alia “programs for computers”) remains unchanged. In particular, it was discussed whether the term “programs for computers” should be deleted from the list in Art. 52(2) EPC. The main argument for not deleting the term was that the possible regulation of patent protection for computer programs by EU law (rejected by the European Parliament on 6 July 2005) should not be anticipated. Below you will find an overview of the travaux préparatoires and of the decisive document.

Travaux préparatoires consist of a plurality of documents

The negotiations leading up to the EPC 2000 are recorded in travaux préparatoires (= official record of the negotiation). The travaux préparatoires consist of the following documents:

- 80 documents prepared by the European Patent Organisation (EPO), national delegations, and user groups. These documents form the basis of the preparatory work which took place mainly in the Administrative Council and in the Committee on Patent Law (body of the Administrative Council). The Administrative Council is one of the two organs of the EPO, the other being the EPO. The Council acts as the Office’s supervisory body and is composed of the representatives of the EPO member states.

- 50 documents submitted for discussion during the 10 days of the Diplomatic Conference in November 2000.

- Minutes of the meetings of the Administrative Council and the Committee on Patent Law.

In the figure below you see an overview about the negotiation process regarding Art. 52 EPC:

The decisive document is disclosed in the following in more detail. The document „Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC (MR/2/00)“ of the travaux préparatoires forms the most important reference document.

“Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC” regarding Art. 52 EPC

The document Basic Proposal for the Revision of the EPC (MR/2/00) was drawn up by the Administrative Council and addresses the Revision Conference for consideration. The document was issued on October 13, 2000.

MR/2/00 is hence – as part of a subsequent agreement between the contracting states concerning the EPC – a valid instrument for construing the Convention according to the traditional rules of interpretation (see decision G 5/83 (supra), Reasons No. 5, rule (4), and the corresponding Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 1969; T 154/04, Reasons, point 8).

The following is an extract from this document MR/2/00, page 43, wherein in the Explanatory remarks all the relevant preparatory documents are listed, thus enabling you to retrieve the legislative history of the provision. The documents of the Explanatory remarks are discussed further below.

MR/2/00: ARTICLE 52 EPC

Explanatory remarks (Preparatory documents: CA/PL 6/99; CA/PL PV 9, points 24-27; CA/PL PV 14, points 143-156; CA/100/00, pages 37-40; CA/124/00, points 12-16; CA/125/00, points 45-73)

- Article 52(1) EPC has been brought into line with Article 27(1), first sentence, of the TRIPs Agreement with a view to enshrining “technology” in the basic provision of substantive European patent law, clearly defining the scope of the EPC, and making it plain that patent protection is available to technical inventions of all kinds.

- In light of the new wording of Article 52(1) EPC, it may be queried whether the provisions of Article 52(2) and (3) EPC, which enumerate subject-matter or activities not to be regarded as inventions, are still needed.

- The Committee on Patent Law and the Administrative Council have advocated the deletion of programs for computers from Article 52(2)(c) EPC. The EPO and the Boards of Appeal have always interpreted and applied the EPC in such a way that this exception in no way excludes appropriate protection for software-related inventions, ie inventions whose subject-matter consists of or includes a computer program. Indeed, more recent decisions of the Boards of Appeal (see T 1173/97 – Computer program product/IBM, OJ EPO 1999, 609) have confirmed that computer programs producing a technical effect, as a rule, are patentable subject-matter under the EPC.

- Nevertheless, the point must be made that patent protection is reserved for creations in the technical field. This is now clearly expressed in the new wording of Article 52(1) EPC. In order to be patentable, the subject-matter claimed must therefore have a “technical character” or to be more precise – involve a “technical teaching”, ie an instruction addressed to a skilled person as to how to solve a particular technical problem using particular technical means. It is on this understanding of the term “invention” that the patent granting practice of the EPO and the jurisprudence of the Boards of Appeal are based. The same considerations apply to the assessment of computer programs. Thus, it will remain incumbent on Office practice and case law to determine whether subject-matter claimed as an invention has a technical character and to further develop the concept of invention in an appropriate manner, in light of technical developments and the state of knowledge at the time.

- Article 52(4) EPC is deleted and transferred to Article 53 EPC (see explanatory remarks to Article 53(c) EPC).

In T 154/04, Reasons, point 8 it is inferred from point 4 above: “The Basic Proposal clearly confirms that patent protection should be available to technical inventions of all kinds (MR/2/00e, page 43, No. 1) and that the technical character is a mandatory requirement for any patentable invention.“

ANNEX II. T 154/04 Estimating sales activity/ DUNS LICENSING ASSOCIATES

In this decision the jurisprudence of the Boards of Appeal on the application of Art. 52, 54 and 56 EPC in the context of subject-matter and activities excluded from patentability under Article 52(2) EPC is summarized. The appellant explicitly disagreed with the “COMVIK approach” applied by the Board for assessing inventive step as it used hindsight to determine the prior art. Furthermore, the Board answers the question whether “methods of business research” are excluded “as such” from patentability under Article 52(2)(c) and (3) EPC.

Summarized jurisprudence of the boards of appeal regarding subject-matter excluded from patentability (reasons, point 5)

(A) Article 52(1) EPC sets out four requirements to be fulfilled by a patentable invention: there must be an invention, and if there is an invention, it must satisfy the requirements of novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability.

(B) Having technical character is an implicit requisite of an “invention” within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC (requirement of “technicality”).

(C) Article 52(2) EPC does not exclude from patentability any subject matter or activity having technical character, even if it is related to the items listed in this provision since these items are only excluded “as such” (Article 52(3) EPC).

(D) The four requirements – invention, novelty, inventive step, and susceptibility of industrial application – are essentially separate and independent criteria of patentability, which may give rise to concurrent objections. Novelty, in particular, is not a requisite of an invention within the meaning of Article 52(1) EPC, but a separate requirement of patentability.

(E) For examining patentability of an invention in respect of a claim, the claim must be construed to determine the technical features of the invention, i.e. the features which contribute to the technical character of the invention.

(F) It is legitimate to have a mix of technical and “non-technical” features appearing in a claim, in which the non-technical features may even form a dominating part of the claimed subject matter. Novelty and inventive step, however, can be based only on technical features, which thus have to be clearly defined in the claim. Non-technical features, to the extent that they do not interact with the technical subject matter of the claim for solving a technical problem, i.e. non-technical features “as such”, do not provide a technical contribution to the prior art and are thus ignored in assessing novelty and inventive step.

(G) For the purpose of the problem-and-solution approach, the problem must be a technical problem which the skilled person in the particular technical field might be asked to solve at the relevant priority date. The technical problem may be formulated using an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field, and which is thus not part of the technical contribution provided by the invention to the prior art. This may be done in particular to define a constraint that has to be met (even if the aim stems from an a posteriori knowledge of the invention).

Technical character (reasons, point 7)

Taking into account object and purpose of the patentability requirements and the legal practice in the contracting states of the EPO, the boards of appeal considered the technical character of the invention to be the general criterion embodied in paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 52 EPC (see, for example, decisions T 22/85 – Document abstracting and retrieving/IBM (OJ EPO 1990, 12), Reasons No. 3, Pension Benefits T 931/95 (supra), Reasons No. 2, and more recently decisions T 619/02 – Odour selection/ QUEST INTERNATIONAL (OJ EPO 2007, 63), Reasons No. 2.2 and T 930/05 – Modellieren eines Prozessnetzwerkes/ XPERT (not published in OJ EPO), Reasons No. 2). By having technical character, any product, method etc., even if formally relating to the list enumerated in paragraph 2, is not excluded from patentability under paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 52 EPC.

Defining the object of the invention (reasons, point 16)

For the purpose of the problem-and-solution approach developed as a test for whether an invention meets the requirement of inventive step, the problem must be a technical problem (see the COMVIK decision T 641/00 (supra), Reasons Nos. 5 ff.). The definition of the technical problem, however, is difficult if the actual novel and creative concept making up the core of the claimed invention resides in the realm outside any technological field, as it is frequently the case with computer-implemented inventions. Defining the problem without referring to this non-technical part of the invention, if at all possible, will generally result either in an unintelligible vestigial definition (DE: unverständliche Rumpfdefinition), or in an contrived statement that does not adequately reflect the real technical contribution provided to the prior art.

The Board, therefore, allowed in COMVIK an aim to be achieved in a non-technical field to appear in the formulation of the problem as part of the framework of the technical problem that is to be solved, in particular as a constraint that is to be met (Reasons No. 7). Such a formulation has the additional, desirable effect that the non-technical aspects of the claimed invention, which generally relate to nonpatentable desiderata, ideas and concepts and belong to the phase preceding any invention, are automatically cut out of the assessment of inventive step and cannot be mistaken for technical features positively contributing to inventive step. Since only technical features and aspects of the claimed invention should be taken into account in assessing inventive step, i.e. the innovation must be on the technical side, not in a non-patentable field (see also decisions T 531/03 – Discount certificates/CATALINA (not published in OJ EPO) Reasons Nos. 2 ff., and T 619/02 (supra), Reasons No. 4.2.2), it is irrelevant whether such a non-technical aim was known before the priority date of the application, or not.

Requirement of inventive step (reasons, points 23-28)

Point 23: For assessing inventive step, the system claims 7 of the main request an auxiliary request 1, and the system claims 1 of auxiliary requests 2 and 3 may be considered together since the technical subject matter of these claims is only marginally different.

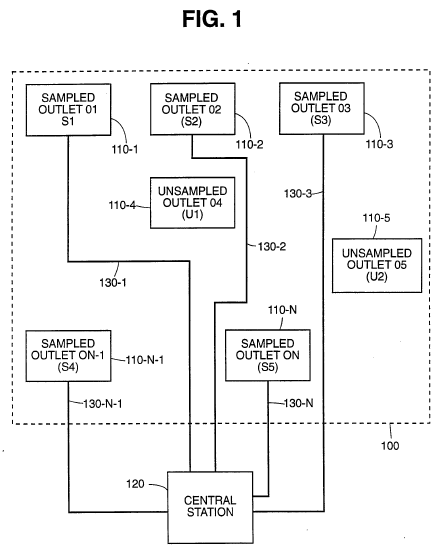

Point 24: The claimed system essentially consists of a central station connected to a plurality of first (reporting) sales outlets providing sales data to the central station for estimating sales (product distribution, sales volume) of at least one other (nonreporting) sales outlet. Regarding such a system, there is general consent that document D1 is a relevant piece of prior art and an appropriate starting point for assessing inventive step.