The first phase of the reform of European design law entered into force on May 1, 2025. The most important changes and innovations are summarized below.

What is the aim?

The reform aims to modernize, clarify, and strengthen design protection. Access to design protection in the EU is to be improved and interoperability of design protection systems in the EU is to be ensured. Furthermore, the different rules on the repair clause are to be harmonized.

What are the most important changes?

– The terminology has been changed from “Community design” to “EU design.”

– Design right holders can now display a design right symbol ‘Ⓓ’ on their products.

– The definition of “design” has been extended to include animations (movement, change of state, or any other form of animation).

– The term “product” now explicitly excludes non-physical objects.

– The infringing acts have been expanded to include “creating, downloading, copying, and sharing or distributing media or software that records a design for the purpose of manufacturing a product in which the design is incorporated or to which the design is applied.” The main aim here is to create a possibility to take action against 3D printing of products for which design protection exists.

– The exhaustion of rights is extended to the territory of the European Economic Area (EEA) (EU + Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway) if a product has been put on the market in this territory by the holder of the EU design or with his consent.

– The exclusive right to a design does not apply to:

o acts carried out for the purpose of identifying or referring to a product as that of the design right holder (aim: product interoperability).

o acts carried out for the purpose of comment, critique or parody, seeking to safeguard the right to freedom of speech.

What changes with regard to the repair clause?

– The transitional repair clause, currently in Article 110 Community Designs Regulation, becomes a permanent provision.

– The new provision specifies that component parts of complex products will not enjoy EU design protection if they are solely used for repairing purposes aimed at restoring the original appearance of the product.

– The scope of application of the repair clause is now clearer: it applies only where the appearance of the component part is dependent on that of the complex product.

– Additionally, it outlines the requirements for spare part manufacturers including the need for sufficient identification of the commercial origin of the product. However, it specifies that they are not obliged to ensure that the component parts they produce or sell are only used for repairing the original appearance of the complex product.

What are the formal changes?

- EU design applications may no longer be filed through National Offices,

- the application fee becomes a filing date requirement,

- possibility of submitting specimens are abolished,

- the unity of class requirement and fee brackets are abolished for multiple applications,

- the unity of class requirement and fee brackets are abolished for multiple applications,

- deferred designs must be surrendered to prevent publication and

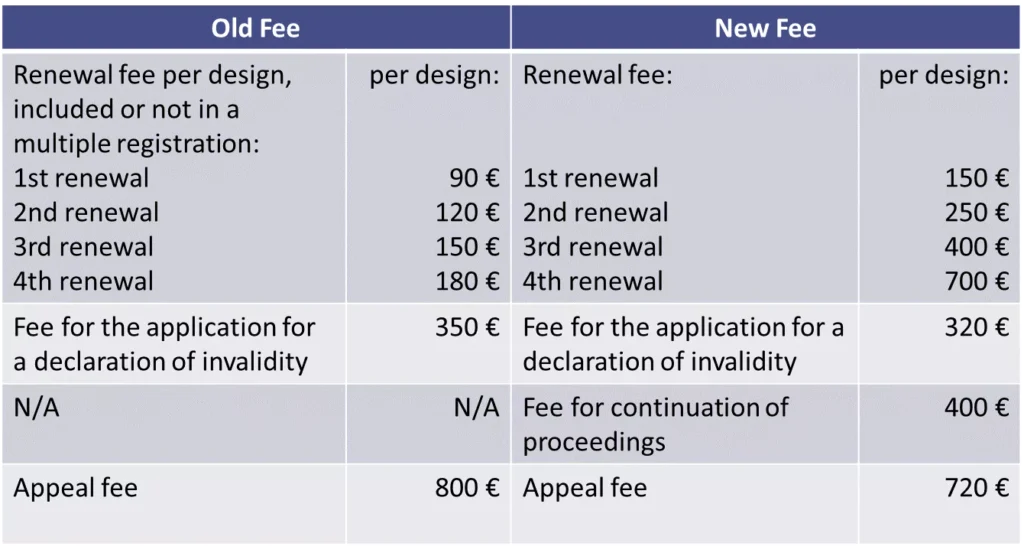

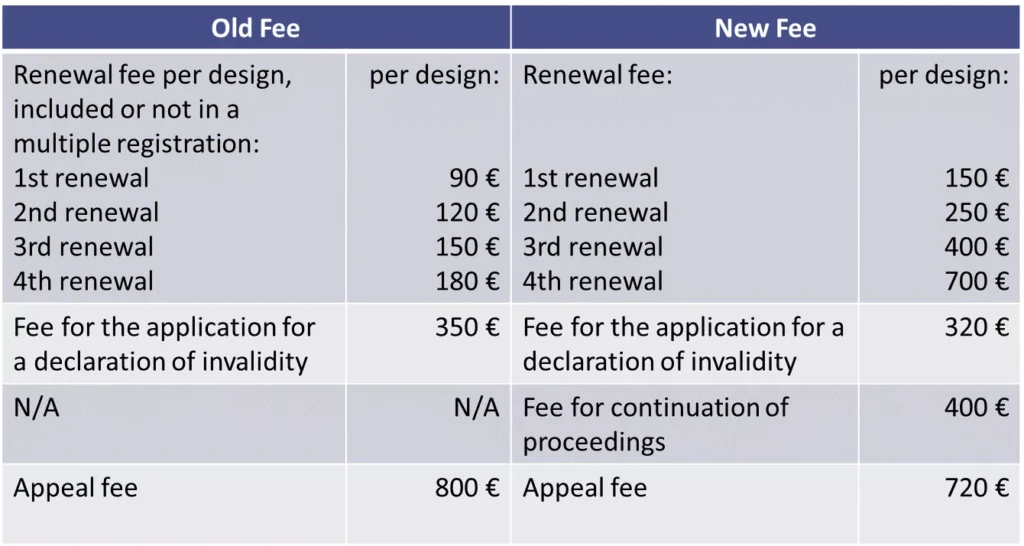

- fees for renewals are increased.

What changes will there be to the fees?

If you have any questions or need more information, please contact us:

>> Contact <<